Trust me. You don't want to be biggest billionaire

Beijing is wary of rich developers because they often load up on debt to fuel expansion, thereby putting corporate China’s financial health at risk

image for illustrative purpose

The ubiquity of Alibaba and Tencent in the economy raises the issue of their monopolistic powers, which can not only choke innovation but also pose systemic risks to Chinese society (that is, the supremacy of the Communist Party)

In China, it's good to be rich, but not too rich. Getting to the top of the billionaire rankings carries great risks. Just take a look at those who were once first among plutocrats. All got into trouble with Beijing - be they real estate developers or big tech bosses.

Wang Jianlin, founder of commercial real estate Dalian Wanda Group Co. Ltd. and China's richest person as recently as 2016, was forced by the government to divest his overseas assets a year later when Beijing began a corporate deleveraging campaign in earnest. Hui Ka Yan, China's richest in 2017, was asked to cut back on debt after his China Evergrande Group, the world's most indebted developer, crossed the country's new "three red lines."

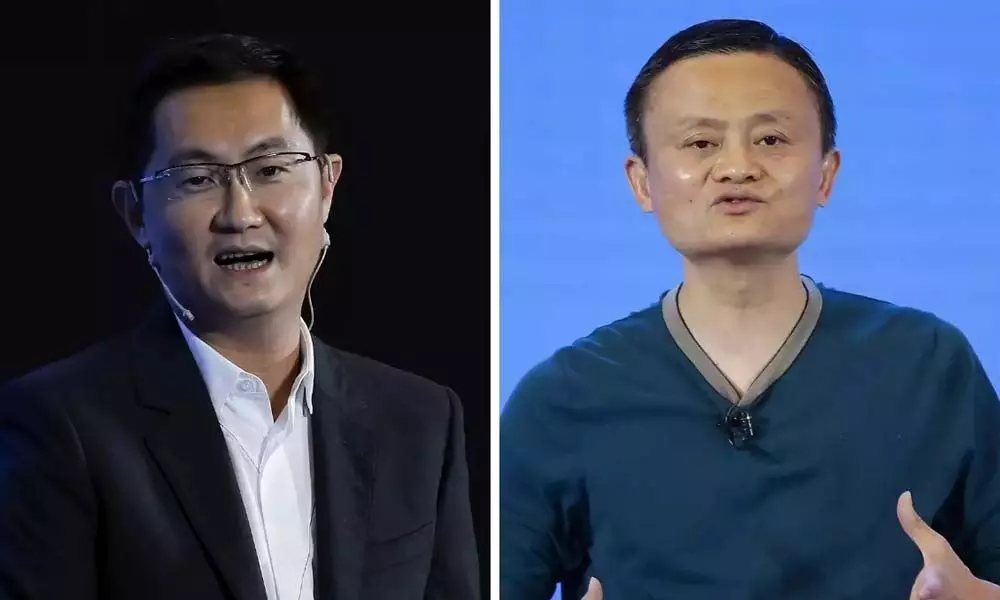

The best known billionaire made an example of by Beijing is, of course, Jack Ma, founder of Alibaba Group Holdings Ltd. According to several news reports, President Xi Jinping personally pulled Ma's $35 billion Ant Group initial public offering in early November, furious with the tech billionaire's blunt criticism of China's State-owned banks. Tencent Holdings Ltd.'s Pony Ma, who in recent years jostled with Jack for the No. 1 slot, has not been spared. He was recently called in by Beijing's watchdogs to discuss antitrust compliance issues.

Conspicuous wealth attracts unwanted scrutiny. Beijing is wary of rich developers because they often load up on debt to fuel expansion, thereby putting corporate China's financial health at risk. The government is just as watchful of Big Tech as it gets bigger. The ubiquity of Alibaba and Tencent in the economy raises the issue of their monopolistic powers, which can not only choke innovation but also pose systemic risks to Chinese society (that is, the supremacy of the Communist Party).

So, what are the smart ways for billionaires to retain their wealth but stay officially correct? Here are three suggestions.

First, give to charity. If you have to be China's richest, you should also be the country's most philanthropical. Take Colin Huang, the founder of Pinduoduo Inc, the e-commerce startup whose sharp stock rally propelled him to No. 4 in the rankings. In terms of active users, the six-year-old company has overtaken Alibaba as the most popular online shopping site. Last summer, he donated a larger than 10 per cent stake in Pinduoduo to charity and scientific research. That, combined with a 2.7 per cent ownership transfer to an early investor, led to a more than $10 billion decrease in his net worth, according to the Bloomberg Billionaire Index. It now stands at $46.3 billion, $16 billion away from Zhong Shanshan, chairman of bottled water company Nongfu Spring Co. Ltd., the current richest person in China. Huang recently stepped down as the company chairman to focus on "life sciences" research, which not only led to a slide in Pinduoduo's shares but personally cost him another $4 billion. (All net wealth and ranking data quoted in this column are as of March 26, 2021 market close.)

I am not belittling Huang's virtue, but moving down the rankings is important in officially socialist China - and philanthropy is a good way to exhibit one's selflessness. It may also have blunted some of the criticism this year at the news of the death of two young employees. That ignited debates over long work hours at big tech companies. Pinduoduo is particularly hard-charging but you can't be too critical of a person who gives his money and time away to medical science?

Huang, however, is no match for Evergrande's Hui. In 2020, with 3 billion yuan in donations, Hui ranked as China's most charitable person, the fourth year in a row, according to Jiemian, a news website. The billionaire was particularly proactive with the Covid-19 epidemic, remitting cash to Wuhan one day after its lockdown and donating millions of dollars to medical research. Hui knows how to calibrate his relationship with Beijing, having engaged in a delicate dance with the government over soaring home prices and his company's debt-fuelled growth.

Second, tinker with your share structure. As I've noted in the past, billionaire rankings around the world are heavily skewed by stock prices, while private wealth - such as an individual's venture capital stakes - is practically ignored. As a result, big tech and green tech billionaires, such Amazon.com Inc.'s Jeff Bezos and Tesla Inc.'s Elon Musk, are now the world's wealthiest. Chinese tech billionaires have to figure out how to contain the way their net worth soars when their company stocks rally in the market. To do this, a dual-class share structure can come in handy. Tech entrepreneurs often use this strategy to retain control as their startups seek rounds of venture capital funding and later a public listing. But Chinese businessmen can use it to suppress their billionaire rankings too.

Let's take a look at Pinduoduo's Huang again. When he was still the chairman, his class B shares - which granted him 10 times the voting rights as class A shares - gave him 80 per cent control in the company. In terms of "beneficial ownership," he had only a 29 per cent stake, because the two share classes have the same economic rights. The 29 per cent stake is what the billionaire rankings look at when they estimate individual net worth. Put another way, if you are an aspiring Chinese unicorn founder on the cusp of a mega-IPO, it pays to have dual-class structure. You get to retain control but minimize the glaring large numbers that will attract Beijing's eye.

Suggestion number three: Don't be shy about setting up conglomerates. Evergrande's Hui has a crown-jewel asset that is unaccounted for in his net worth. He owns over 70 per cent of China Evergrande Group, which in turn holds over 70 per cent of China Evergrande New Energy Vehicle Group. As part of the global green tech rally, his EV subsidiary's market value has soared by over 1,000 per cent in the last year to $76 billion, well above its parent's $25 billion market cap. Using rough estimates, if Hui's net worth was based on the EV unit - assigning zero equity value to all his other businesses - he would be the fifth-richest person in China. However, in the billionaire rankings, Hui only gets credit for his stake in China Evergrande Group - and so he is about $20 billion poorer! Thanks to the conglomerate discount, he is now blissfully China's 13th richest man, with a net worth of only $23 billion. And what about China's biggest billionaire? Shouldn't the bottled water tycoon be nervous? First, Zhong isn't in the volatile real estate and technology sectors.

He's also a do-gooder: Zhong has controlling stakes in a vaccine and hepatitis test-kit maker. Finally, if he decides being No. 1 isn't for him, he can climb down the billionaire listings simply by parting with some of his 84 per cent stake in the company. He won't lose anything tangible. His wealth is an accounting matter. He can sleep easy. (Bloomberg)